Brad Evans: I Know I Will Never Write a Better Book

If the measure of writing is to get as close as we can to the truth of existence, I know I will never write a

This is an edited extract from From a Whisper to a Shout: Abortion Activism and Social Media, out now from Repeater.

Abortion. Can we finally stop whispering about it?

Abortion has been around almost as long as pregnancy. Historical records show separate references to abortion techniques as long ago as 3000 years BCE in Egypt, Greece, and China, and major world religions did not forbid it. Even the Catholic Church permitted abortion until the moment of ensoulment, believed to occur at the time of quickening, the first time the pregnant person can feel movement of the fetus. No one before the nineteenth century believed abortion was taking a human life. Traditional Hebrew religious law did not consider a woman pregnant until forty days after conception, allowing a window in which abortion was morally acceptable. Some classical interpretations of the Quran permitted abortion before ensoulment, defined here as the moment when an angel breathes the spirit into the fetus at 120 days, while other interpretations approved abortion conditionally for valid reasons. Still other schools of Islam forbade abortion entirely.

As a secular society, the US history of abortion is mostly the history of its regulation. Pregnancy termination was widely practiced but completely unregulated in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. An induced abortion before quickening wasn’t even considered an abortion but a pregnancy that had “slipped away”. The earliest regulations, such as Connecticut’s 1821 law, the first on record, were legislated to protect women from being poisoned by dangerous abortifacient drugs sold by unscrupulous vendors. These early laws were poison-control measures, not abortion restrictions, and they did not challenge the concept of quickening or women’s right to make decisions about their pregnancies. Their autonomy over their bodies was preserved by what the law omitted. By the mid-nineteenth century, the emerging medical profession sought to restrict abortion to take control of the procedure — and everything else related to pregnancy — away from women and midwives.

The American Medical Association (AMA) was formed in 1847 and provided physicians with an infrastructure from which to organize an anti-abortion campaign. The basis of the campaign was professional issues, as the organization moved to medicalize pregnancy and childbirth; but from the vantage point of the twenty-first century, racist and anti-feminist messages are easy to read in some early anti-abortion campaigns. Dr Horatio R. Storer, a prominent advocate of banning abortion, expressed anxiety about Mexicans, Chinese, Blacks, Indians, or Catholics spreading into the American West instead of native-born white Americans. He was opposed as well to the concurrent push from women to enter medical school. Storer also took issue with quickening: he argued that it is not a fact or a medical diagnosis, “but a sensation” based on women’s bodily sensations, leaving doctors dependent on women’s judgment and self-understanding.

By 1890 abortion was criminalized in every state, although it wasn’t treated exactly the same in each. In some places it was permitted only when necessary to save the life of the woman, while in other areas women could receive an abortion in a doctor’s office or even at home. The latter practice ended in the mid-twentieth century as new methods of controlling abortion were implemented by medical and legal authorities. By this point in the 1950s, somewhere between 200,000 and 1.2 million illegal, unsafe abortions were performed every year, according to Dr David Grimes, a former chief of the Abortion Surveillance Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It was also mid-twentieth century when activists began to work for the repeal of abortion laws and restrictions. This grassroots movement pre-dates what is now known as second-wave feminism.

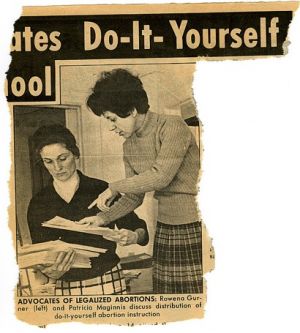

The first activists to advocate for abortion access in terms of women’s rights, Patricia Maginnis, Lana Phelan, and Rowena Gurner, came together in California in the early 1960s — first Maginnis and Gurner in 1961, with Phelan joining in 1965. The group they formed, the Society for Humane Abortion (SHA), worked tirelessly for more than a decade to educate the public about the issues. They delivered presentations about abortion at conferences and in classes, and in 1969 published the satirical guide The Abortion Handbook for Responsible Women. To maintain SHA’s tax-exempt status, they created a second group, Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (ARAL), which eventually grew into the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (NARAL). After the 1973 US Supreme Court decision legalizing abortion, the group’s new leadership shifted its focus to keeping abortion “safe and legal” and changed its name to National Abortion Rights Action League (still NARAL). In 2003, the organization changed its name to NARAL Pro-Choice America, stating that they faced a hostile political climate for abortion and the new name “underscore[s] that our country is pro-choice”, according to then-president Kate Michelman. It’s surely no coincidence that the new name completely omitted the word abortion.

Several US states revoked criminalization of abortion and allowed termination of pregnancy before twenty weeks in 1970: first Hawaii, then New York, Alaska, and Washington. Also in 1970, a young, impoverished Texas woman named Norma McCorvey found herself unintentionally pregnant for the third time and challenged the state law prohibiting abortion. Texas laws were then the most restrictive in the nation. Because both abortion and unmarried pregnancy were considered so shameful, she was referred to in court documents as Jane Roe to protect her privacy. By the time the US Supreme Court ruled in her favor, on January 22, 1973, it was too late for her to abort, but Roe v. Wade made it legal for every pregnant person in the country to make a decision to end a pregnancy in the first two trimesters, for any reason.

It must be recognized, however, that Roe was decided on the basis of the right to privacy, grounded in the Fourteenth Amendment and judicial precedent, not on the basis of equality. Numerous critics, including current Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, have commented on how the decision “is as much about the doctor’s right to recommend to his patient what he thinks his patient needs. It’s always about the woman in consultation with her physician and not the woman standing alone in that case.”

Abortion opponents soon began working to limit abortion access, and in 1976 Congress passed Illinois representative Henry Hyde’s proposed prohibition of Medicaid funds for abortion for indigent women. The constitutionality of the Hyde Amendment has been upheld repeatedly, even its prohibition of medically necessary abortion. Activists working today from a reproductive justice framework note that while the right to privacy is now well established, it is essentially a negative right; that is, a right to be left alone. No positive right to abortion is established, making it functionally accessible only to those who can afford it.

In the forty-four years since the 1973 Supreme Court ruling, individual states have enacted 1,074 abortion restrictions. Of these, 353 (27%) have been enacted just since 2010. Restrictions include mandating medically inaccurate or misleading counselling prior to the procedure; requiring a waiting period after abortion counselling, thus necessitating at least two trips to the facility; mandating a medically unnecessary ultrasound exam before an abortion; banning Medicaid funding of abortion (except in cases of life endangerment, rape or incest); restricting abortion coverage in private health-insurance plans; requiring onerous and unnecessary regulations on abortion facilities; imposing medically inappropriate restrictions on medication abortion; and imposing an unconstitutional ban on abortion before viability or limits on abortion after viability. In this climate, talking about abortion is ever more important — to break abortion stigma and to keep abortion safe, legal, and accessible, abortion must be visible. Instead, abortion has been increasingly stigmatized and shamed since Roe v. Wade was decided.

…

Organizational/structural stigmas include such examples as the way abortion is physically separated from other healthcare, including gynecological and obstetric care, and inconsistent training available in medical schools. The community level of stigma includes the risk of being labelled promiscuous or careless or worse, another illustration of how abortion is highly stigmatized in the US. Individual-level stigma may be the most variable, as personal experience varies; the discourses of stigma in the community, organizations, government/structures, and media frequently influence individual psyches and experiences. All of these are discursive; that is, created and maintained through language and communication. This discursivity is integral to how they work.

For instance, consider the idea that abortion is stigmatized because it contradicts “ideals of womanhood”. Kumar et al. identify three archetypes that characterize the so-called essential nature of woman in the popular imaginary: a sexuality focused on procreation rather than pleasure; the inevitability of motherhood; and a nurturing instinct. When a woman voluntarily terminates a pregnancy, she is believed to be rejecting all of those archetypes — even though a majority of women who have abortions (59%) are already mothers and the most common reasons cited for seeking abortion are about family responsibilities. Yet voluntarily terminating a pregnancy challenges the moral order of patriarchal culture. In a recent interview with the Washington Post, Cecile Richards, president of Planned Parenthood, named other beliefs about women that abortion decisions and access challenge: “There’s this thought that women are just too scattered, we’re too impulsive, we are too hormonal, we can’t make good decisions for ourselves”.

Most central, according to theories of abortion stigma, is the implicit tension about female sexuality: when, why, how, with whom. Did she use contraception? (That means she intended to have sex!) Is she too young? (She’s not ready to make this decision!) Did she choose the wrong man? (Perhaps someone others think is wrong for her.) And so on. Legislation regulating abortion is the most overt example of language that judges women for deviance from these feminine archetypes and further stigmatizes abortion with the lingering stain of criminality.

This is not to suggest that women are themselves ashamed of sex or sexuality, or even that all women feel stigma about abortion. Those who have terminated pregnancies are a heterogeneous group — in no small part because they are a large group. More than one million women in the US have abortions each year and estimates are that by age forty-five one-third of women will have had an abortion. It is also believed by demographers that abortion in the US is underreported. But abortion secrecy rules are well documented: two of three abortion patients anticipate experiencing stigma and a similar number (58%) feel the need to keep their decision from friends and family — an unfortunate trend, as social support is a mitigating factor in experiencing stigma. The pressure to keep abortion secret is strong enough that even when the procedure is covered by private insurance (about 30% of cases) two-thirds of those patients will pay out-of-pocket rather than have it appear on their medical and insurance records. This may be another factor in heightened stigma in the US; anecdotal evidence suggests that abortion is less stigmatized in the UK, where it is covered by the National Health Service.

Norris et al. (2011) suggest that additional reasons for abortion stigma may lie in the discourse of personhood attributed to the fetus. Advances in fetal medicine, such as 3D fetal photography and advanced fetal surgery, have facilitated this, as has the proliferation of anti-abortion legislation.

Morality and medicine, like fact and fiction, are entangled in many of these state laws enacted to restrict access to abortion. The Guttmacher Institute (2016), a research and policy organization focused on sexual and reproductive health and rights, reports that at least half of the fifty states have imposed regulations designed to deter women, such as mandatory counselling, required waiting periods, required parental involvement for minors, mandatory ultrasound imaging, and prohibitions on the use of Medicaid funds. A separate report documents the proliferation of regulations known as TRAP laws (Targeted Regulations of Abortion Providers), which focus specifically on clinics and providers, mandating clinic requirements in such categories as corridor widths, distance from hospitals, admitting privileges for providers, and more. A 2016 US Supreme Court decision (Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt) struck down the latter type of regulations. The state law in question had already closed nearly two dozen clinics in Texas since 2013. In the three years since the law took effect, an estimated 100,000 Texas women have self-induced abortions. The number could be more than twice that, depending on how it is calculated. The court’s ruling in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt concluded “that neither of these provisions offers medical benefits sufficient to justify the burdens upon access that each imposes. Each places a substantial obstacle in the path of women seeking a previability abortion [and] each constitutes an undue burden on abortion access”, as well as being violations of the Constitution.

Many state regulations seem frankly designed to shame and stigmatize, as well as impose additional burdens on the process. Some regulations appear intended to influence women against abortion with bad science. For example, six states require abortion providers to advise women that the procedure can result in severe mental health consequences, despite repeated research showing this is not true. Yet no state requires that pregnant people be informed of the research linking unintended pregnancy and childbearing with adverse mental health outcomes. Kansas, Texas, South Dakota, and Arizona require that the pre-abortion counselling session include a statement that abortion may harm their ability to conceive in the future. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has affirmed that “that one abortion does not affect your ability to get pregnant or the risk of future pregnancy complications”. Five states still mandate that materials or counselling be provided informing women of a potential link between abortion and breast cancer — a link that was debunked almost fifteen years ago when the National Cancer Institute convened a workshop of more than a hundred of the world’s experts on the subject, who concluded that abortion does not increase a woman’s risk of breast cancer. This finding has been affirmed by ACOG and the American Cancer Society, as well as a panel convened by the British government in 2004.

Equally egregious and insulting are the mandatory waiting periods, required in twenty-seven states. These “cooling-off periods” range from eighteen hours to three days after pre-abortion counselling before patients can receive an abortion, and usually exclude weekends and holidays. These regulations are based on the belief that women choose impulsively to terminate an unintended pregnancy, or perhaps have not considered the full impact of their choice; that is, that upon termination, they will no longer be pregnant. State legislators presume that women cannot make good decisions. Research has shown that women are actually less conflicted in abortion decisions than people making decisions about other medical procedures. A recent study of Utah’s seventy-two-hour waiting period found that most clients (91%) were just as certain after the three-day wait; 17% reported that waiting made them more certain. Previously published studies by the same researchers have shown that waiting periods increase the cost of the abortion and cause logistical hardships for patients. Civil rights lawyer Danielle Lang (2016) writes, “The argument goes as follows: Women, whose natural role is mother, would never in their right mind seek to terminate a pregnancy. Their choice therefore must be a result of bad influence, coercion or undue pressure.” Fifteen states even require pre-abortion counselling to inform the woman that she cannot be coerced into obtaining an abortion. It’s difficult to imagine other medical procedures being treated in this fashion, such as a three-day waiting period to have an aching tooth pulled or gaping wound stitched up, with a warning that no one can compel you to have those stitches. In his recently published memoir, abortion provider Dr Willie Parker extends the comparison to cancer, writing:

A woman who decides not to pursue treatment and to shorten her life in order to be clear-minded for as long as possible is considered “brave”. A woman who decides to take radical action, to undergo surgeries and try every experimental drug in the pipeline is a “warrior”. Even patients with lung cancer are not blamed and judged for smoking in the same way that women who seek abortions are blamed for having sex.

These regulations may individually seem minor, but their impact and reach are significant. Gold and Nash (2017) point out that seventeen states have at least five types of these restrictions that flout scientific evidence, and 30% of US women of reproductive age live in those states. Their review examines ten categories of restrictions; 53% of US women live in a state that has at least two of these restrictions.

In addition, abortion stigma has been effectively weaponized by anti-abortion activists. Protestors have used shaming and insulting language — such as calling patients “murderer” and “slut” as they enter clinics — and created overt barriers at clinics across the country. Despite the FACE Act (Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances) and the presence of volunteer escorts, anti-abortion zealots regularly show up at clinics to engage in prayer vigils and so-called sidewalk counselling, as well as to mob the cars and taxis of clinic patients and their companions and to photograph patients and providers without permission. “Sidewalk counselling” often consists of repeated interrogation about whether the patient has Jesus in her life, or slut shaming. A 2017 mini-documentary about clinic protestors produced by Rewire News shows anti-abortion activists acknowledging that they write down license plate numbers of clinic staff, which prompts anxiety and fear among clinic employees.

Abortion stigma reaches beyond those who have the procedure: abortion providers and clinic workers also experience it, albeit of a somewhat different nature. This has to do in part with structural forces of current medical practice. For instance, most abortions occur in women’s health clinics, which increases their isolation from the rest of healthcare. This was initially a strategic choice by proponents to maintain sensitive and women-controlled care of patients. Today it has made providers easy targets – literally and metaphorically – for abortion opponents. They are subject to harassment and violence and their clinics are singled out for regulations that other kind of outpatient medical facilities are not. The scarcity of abortion providers today results in some doctors becoming de facto abortion specialists (which is not inherently troublesome, as many physicians and surgeons develop expertise in particular procedures). The stigma is greater if they perform second-trimester abortions. Although providers experience these sources of abortion stigma on a continual basis, they can counter them with belief in the value and necessity of their work. On the other hand, unwillingness to disclose their work in public or social settings can increase the perception that abortion work is unusual or deviant, and reinforce the stigma. Family and friends of the patient may also experience abortion stigma. Male partners have reported ambivalence, guilt, sadness, anxiety, powerlessness — the same range of emotions felt by women who seek abortions.

Kumar has cautioned researchers to avoid “conceptual inflation” in defining abortion stigma, noting the importance of separating stigma analytically from prejudice and discrimination as it is both a cause and a consequence of inequality. To understand the power dynamics, the concept must be narrowly defined. When abortion is highly politicized, as in the US, “greater conceptual clarity is needed on the power differentials that create and maintain abortion stigma such as those related to race, age, and class”.

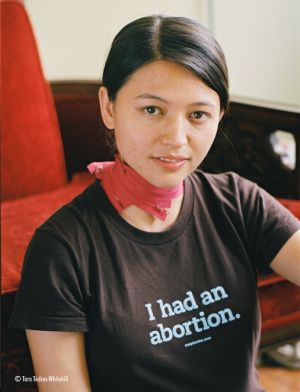

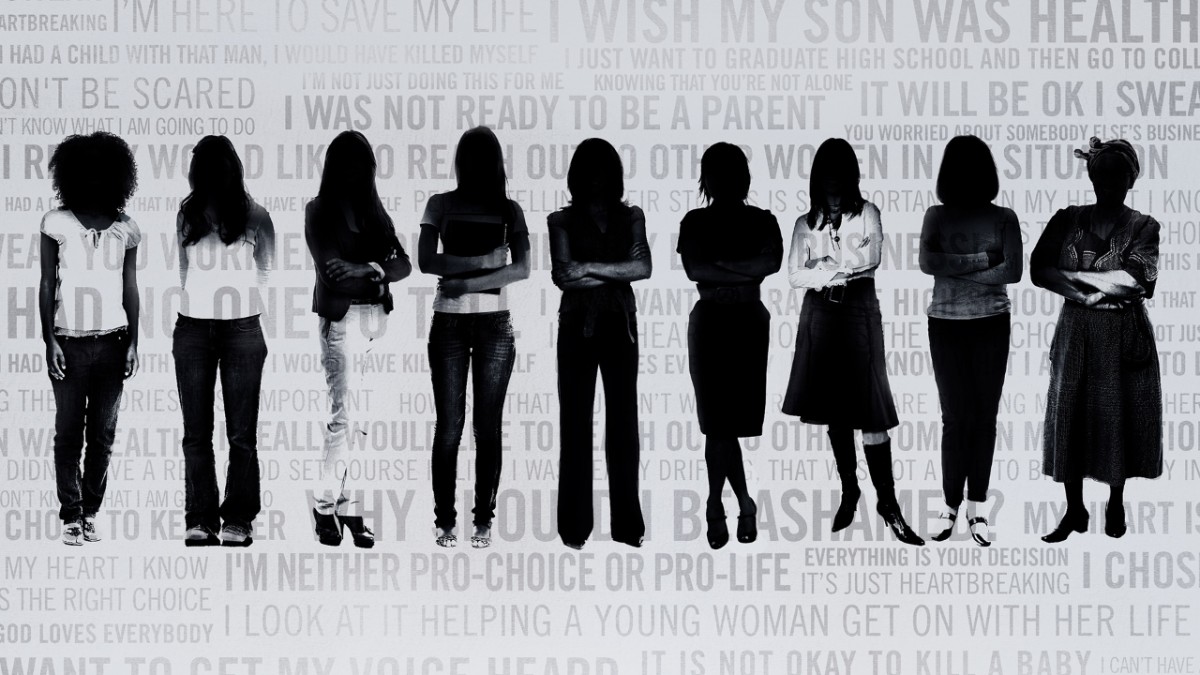

The precise nature of abortion stigma comes into clearer focus upon examination of women’s stories of abortion experience. Two documentary films released in 2005 featured personal stories of abortion: I Had an Abortion by Jennifer Baumgardner and The Abortion Diaries by Penny Lane. Both films had the explicit purpose of making abortion narratives public, widely shared, and without shame. Both films feature individuals stating that the shame of unintended pregnancy is greater than the shame of abortion. Joh in The Abortion Diaries tells her interviewer it was upsetting to her “that somebody knew that I’d messed up. ’Cause that’s what it was considered, that if you got pregnant, you messed up.” Baumgardner reports a male friend who has been part of more than one abortion (not uncommon for an urban, single, heterosexual dude approaching forty) who says it’s not the abortion that’s shameful, it’s the pregnancy. A 2016 HBO film, Abortion: Stories Women Tell by Tracy Droz Tragos, shows little change in the intervening decade. While the new film differs from those from 2005 in that it includes stories of women who elected to continue their pregnancies and stories of abortion protestors as well as abortion stories, the theme of abortion stigma is still strong. In a Newsweek interview, Tragos references all the women she spoke with who could not tell their stories on camera, fearing repercussions at work or at home, saying they found “some solace in even talking about [it] and being heard”.

The precise nature of abortion stigma comes into clearer focus upon examination of women’s stories of abortion experience. Two documentary films released in 2005 featured personal stories of abortion: I Had an Abortion by Jennifer Baumgardner and The Abortion Diaries by Penny Lane. Both films had the explicit purpose of making abortion narratives public, widely shared, and without shame. Both films feature individuals stating that the shame of unintended pregnancy is greater than the shame of abortion. Joh in The Abortion Diaries tells her interviewer it was upsetting to her “that somebody knew that I’d messed up. ’Cause that’s what it was considered, that if you got pregnant, you messed up.” Baumgardner reports a male friend who has been part of more than one abortion (not uncommon for an urban, single, heterosexual dude approaching forty) who says it’s not the abortion that’s shameful, it’s the pregnancy. A 2016 HBO film, Abortion: Stories Women Tell by Tracy Droz Tragos, shows little change in the intervening decade. While the new film differs from those from 2005 in that it includes stories of women who elected to continue their pregnancies and stories of abortion protestors as well as abortion stories, the theme of abortion stigma is still strong. In a Newsweek interview, Tragos references all the women she spoke with who could not tell their stories on camera, fearing repercussions at work or at home, saying they found “some solace in even talking about [it] and being heard”.

Smith et al.’s recent interview study of reproductive decisions among young women in the American South found stigma attached to both pregnancy and abortion. Within their Alabama communities, “young women faced with an unintended pregnancy were often deemed ‘fast’ and labelled ‘heathens’ or ‘whores.’ Participants described how women can be the target of accusations and gossip regardless of their pregnancy decision”. A few participants reported losing friends when others, especially parents of their friends, learned of their pregnancies. Interview studies of adult women have also found women reporting disapproving attitudes from friends and family members, as well as loss of friends and boyfriends over abortion decisions. Reproductive justice activist Loretta J. Ross (2016) suggests that respectability politics today leads to more abortion shaming in our era of accessible birth control and legal abortion because now women are seen as both moral and intellectual failures for not using contraception, whereas a previous generation of young women with few options might be chastised only for their risky abortions.

Shame and secrecy surround nearly every reproductive health event; menstruation and menstrual disorders, miscarriage, and breastfeeding all follow widespread cultural norms of concealment and secrecy. For instance, Seear (2009) reported average diagnostic delays of eight years in the UK and eleven years in the US for endometriosis, due largely to stigma that normalizes menstrual pain and enforces silence. Miscarriage is also difficult to discuss and widely misunderstood, yet common: it occurs in about one-fourth of pregnancies in the US but 55% of Americans believe that it is rare. A national survey about miscarriage found that while most respondents knew that genetic malformation is a possible cause of miscarriage, substantial numbers agreed with the following incorrect causes: lifting heavy objects (64%), having had a sexually transmitted disease in the past (41%), past use of an IUD (28%), past use of oral contraception (22%), or getting into an argument (21%). Among survey respondents who had experienced miscarriages, 47% reported feeling guilty, 41% reported feeling that they did something wrong, 41% reported feeling alone, and 28% reported feeling ashamed.

This reproductive secrecy imposes a norm of silence around any reproductive experience that does not meet patriarchal ideals of femininity, such as adhering to the roles of good wife and good mother; in other words, there is no acceptable social discussion of miscarriages, abortions, or the decision to be childless by choice. The invisibility of these common experiences belies how normal they are. For example, many women in Gelman et al.’s study did not learn how common abortion is until they had one. They told researchers how surprised they were at the packed waiting rooms, expecting that “it would be me and maybe like one or two other people”, as one informant said.

Ellison suggests that this “cultural censorship of an experience shared by so many women reinforces an inflexible tension between cultural ideals and women’s lived realities”. This can be seen easily among Smith et al.’s young informants, who report that unintended pregnancy is both shamed and a common occurrence in their communities. These young women learn to regard abortion as even more shameful, reporting that they’ve been told abortion is irresponsible, immoral, selfish, and “you’ll get sick”, making abortion invisible in these communities. The women told the researchers stories of friends and family members who had obtained secret abortions and of miscarriages that they suspected were “hidden” abortions.

While the rate of unintended pregnancy has declined considerably over the last decade, it is still a common occurrence everywhere in the US, at 45% of all pregnancies. Twenty-one percent of all pregnancies end in abortion, leading to an annual total of more than one million pregnancy terminations. Both abortion and unintended pregnancy show a downward trend, with the most likely explanation “a change in the frequency and type of contraceptive use over time”, especially long-acting hormonal methods such as IUDs. At current rates, one of every four American women is likely to have an abortion by age thirty, and one in three by age forty-five.

But abortion stigma and shaming of women who seek abortions, their supporters, and abortion providers shows little decline. There is, however, a bold new movement of feminist activists challenging and resisting abortion stigma. These groups rely heavily on the internet and social media platforms to share stories and inform others about pending legislation and judicial decisions, as well as to promote participation in traditional activism, such as protests, meetings, and rallies. One of their shared goals is to normalize abortion by talking about it. These groups include #ShoutYourAbortion, Lady Parts Justice, We Testify, The Abortion Diary, 1 in 3 Campaign, Sea Change, Shift (affiliated with Whole Woman’s Health Alliance), My Abortion My Life (a project of PreTerm clinics of Ohio), Rewire, URGE (Unite for Reproductive and Gender Equality, which uses the hashtag #AbortionPositive), Abortion Story Project, Project Voice, and probably many more. In the interest of time and space, I will focus here on #ShoutYourAbortion, Lady Parts Justice, We Testify, The Abortion Diary, and 1 in 3 Campaign. These five were selected partly for convenience, but also because they are among the most visible of these groups and they represent use of diverse social media channels: Twitter, YouTube, Facebook, websites, and podcasts.

#ShoutYourAbortion (SYA) is, according to their website, a “decentralized network of individuals talking about abortion on their own terms and creating space for others to do the same”. The SYA slogan says, “Abortion is normal. Our stories are ours to tell. This is not a debate.” The hashtag emerged in 2015, from a Twitter conversation between Amelia Bonow and Lindy West, in response to a congressional vote to defund Planned Parenthood. Bonow wrote on Facebook about how grateful she was to have had abortion accessible at her local Planned Parenthood affiliate when she needed one the previous year, and with her permission, West shared her story on Twitter, with the hashtag #ShoutYourAbortion.

Lady Parts Justice (LPJ) was founded by comic Lizz Winstead, filmmaker Arun Chaudhary, and marketing CEO Scott Goodstein. LPJ and their sister organization, Lady Parts Justice League (LPJL), produce satirical, informative videos about anti-reproductive rights legislation, including parodies of popular songs and television shows re-worked with messages related to current abortion legislation. LPJL provides USO-style support to independent clinics all over the country, performing comedy shows that serve as entertainment for clinic employees and as fundraisers for clinic needs, often in regions that seldom see popular comedy performers tour. LPJL has also helped escort patients, planted a protective prickly bush in a fencing gap to block protesters, painted fences, counter-protested anti-choice activists, and thrown dance parties in parking lots for escorts and staff.

We Testify, a program initiated by the National Network of Abortion Funds, “is dedicated to increasing the spectrum of abortion storytellers in the public sphere and shifting the way the media understands the context and complexity of accessing abortion care”. It is a leadership program designed to support people of color in building their power and telling their stories. Renee Bracey Sherman, We Testify Program Manager, is the author of a resource guide for public abortion storytelling published by Sea Change.

The Abortion Diary podcast was started by Melissa Madera in the summer of 2013, after Madera had kept her abortion experience secret for thirteen years and seen the impact that finally telling her story had on her family, her friends, and herself. She chose the platform of podcasting to create a safe space for sharing stories “because, more than anything else, I wanted to listen”. By the beginning of 2017, she had collected more than two hundred abortion stories.

The 1 in 3 Campaign is the oldest abortion story project on the internet, and features the largest set of abortion stories published online, and the only bilingual collection, with stories published in English and in Spanish. More than a storytelling platform, 1 in 3 is also an organizing hub for college students working on reproductive justice issues on their campuses. It was created in 2011 by Advocates for Youth, an organization dedicated to supporting sexual and reproductive rights for young people.

Each has unique strengths and emphases. For instance, #ShoutYourAbortion centers visibility and politics of recognition, while Lady Parts Justice uses feminist humor as a tool of political analysis, and We Testify and the 1 in 3 Campaign use story-sharing to politicize themselves and others. All are working to normalize abortion, as they politicize supporters through narrative, online outreach, activism, and consciousness raising. For imagining a world without abortion stigma does not require that we celebrate abortion, only that we acknowledge it openly and without shame. A world without abortion stigma is also a world in which women can experience a vibrant sexuality, including access to comprehensive birth control and reproductive health services without shame, and one in which talking about those experiences is neither forbidden nor required.

If the measure of writing is to get as close as we can to the truth of existence, I know I will never write a

To accompany his latest piece with Tariq Goddard in The Quietus on True Detective Season 4 and the legacy of In The Dust of This Planet, Eugene

As another turbulent year draws to a close, the Repeater team put forward their favourite reads for the festive season. Publisher, Editor, and Author Tariq

If the measure of writing is to get as close as we can to the truth of existence, I know I will never write a

To accompany his latest piece with Tariq Goddard in The Quietus on True Detective Season 4 and the legacy of In The Dust of This Planet, Eugene

As another turbulent year draws to a close, the Repeater team put forward their favourite reads for the festive season. Publisher, Editor, and Author Tariq