Brad Evans: I Know I Will Never Write a Better Book

If the measure of writing is to get as close as we can to the truth of existence, I know I will never write a

The word grotesque derives from a type of Roman ornamental design first discovered in the fifteenth century, during the excavation of Titus’s baths. Named after the ‘grottoes’ in which they were found, the new forms consisted of human and animal shapes intermingled with foliage, flowers, and fruits in fantastic designs which bore no relationship to the logical categories of classical art. For a contemporary account of these forms we can turn to the Latin writer Vitruvius. Vitruvius was an official charged with the rebuilding of Rome under Augustus, to whom his treatise On Architecture is addressed. Not surprisingly, it bears down hard on the “improper taste” for the grotesque: “Such things neither are, nor can be, nor have been,” says the author in his description of the mixed human, animal, and vegetable forms: “For how can a reed actually sustain a roof, or a candelabrum the ornament of a gable? Or a soft and slender stalk, a seated statue? Or how can flowers and half-statues rise alternately from roots and stalks? Yet when people view these falsehoods, they approve rather than condemn, failing to consider whether any of them can really occur or not.”

— Patrick Parrinder, James Joyce

If Wells’ story is an example of a melancholic weird, then we can appreciate another dimension of the weird by thinking about the relationship between the weird and the grotesque. Like the weird, the grotesque evokes something which is out of place. The response to the apparition of a grotesque object will involve laughter as much as revulsion, and, in his study of the grotesque, Philip Thomson argued that the grotesque was often characterised by the co-presence of the laughable and that which is not compatible with the laughable. This capacity to excite laughter means that the grotesque is perhaps best understood as a particular form of the weird. It is difficult to conceive of a grotesque object that cannot also be apprehended as weird, but there are weird phenomena which do not induce laughter — Lovecraft’s stories, for example, the only humour in which is accidental.

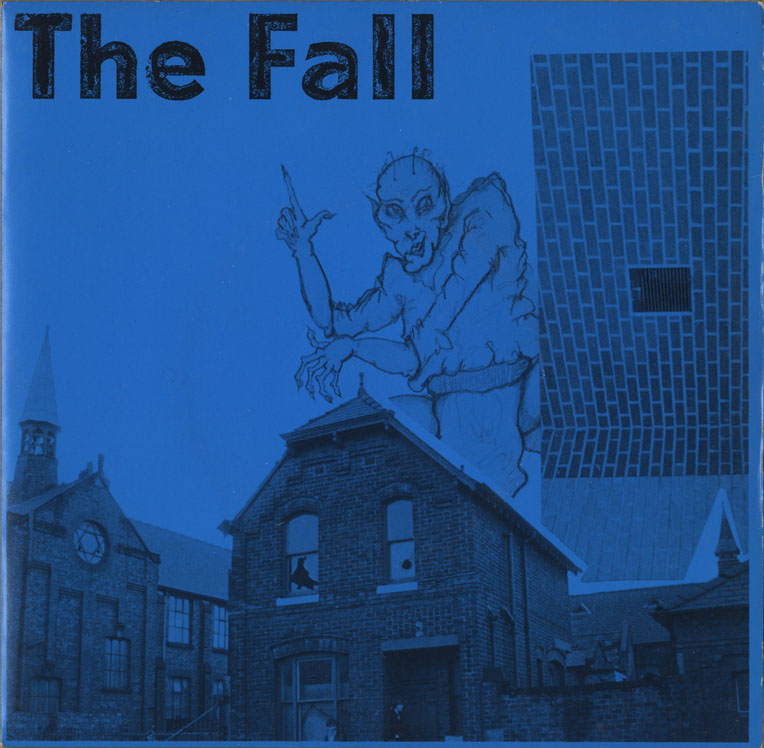

The confluence of the weird and the grotesque is no better exemplified than in the work of the post-punk group The Fall. The Fall’s work — particularly in their period between 1980-82 — is steeped in references to the grotesque and the weird. The group’s methodology at this time is vividly captured in the cover image for the 1980 single, “City Hobgoblins”, in which we see an urban scene invaded by “emigres from old green glades”; a leering, malevolent cobold looms over a dilapidated tenement. But rather than being smoothly integrated into the photographed scene, the crudely rendered hobgoblin has been etched onto the background. This is a war of worlds, an ontological struggle, a struggle over the means of representation. From the point of view of the official bourgeois culture and its categories, a group like The Fall — working class and experimental, popular and modernist — could not and should not exist, and The Fall are remarkable for the way in which they draw out a cultural politics of the weird and the grotesque. The Fall produced what could be called a popular modernist weird, wherein the weird shapes the form as well as the content of the work. The weird tale enters into becoming with the weirdness of modernism — its unfamiliarity, its combination of elements previously held to be incommensurable, its compression, its challenges to standard models of legibility — and with all the difficulties and compulsions of post-punk sound.

Much of this comes together, albeit in an oblique and enigmatic way, on The Fall’s 1980 album Grotesque (After the Gramme). Otherwise incomprehensible references to “huckleberry masks”, “a man with butterflies on his face”, “ostrich headdress” and “light blue plant-heads” begin to make sense when you recognise that, in Parrinder’s description quoted above, the grotesque originally referred to “human and animal shapes intermingled with foliage, flowers, and fruits in fantastic designs which bore no relationship to the logical categories of classical art”.

The songs on Grotesque are tales, but tales half-told. The words are fragmentary, as if they have come to us via an unreliable transmission that keeps cutting out. Viewpoints are garbled; ontological distinctions between author, text and character are confused and fractured. It is impossible to definitively sort out the narrator’s words from direct speech. The tracks are palimpsests, badly recorded in a deliberate refusal of the “coffee table” aesthetic that the group’s leader Mark E. Smith derides on the cryptic sleeve notes. The process of recording is not airbrushed out but foregrounded, surface hiss and illegible cassette noise brandished like improvised stitching on some Hammer Frankenstein monster. The track “Impression of J Temperance” was typical, a story in the Lovecraft style in which a dog breeder’s “hideous replica”, (“brown sockets… purple eyes … fed with rubbish from disposal barges…”) stalks Manchester. This is a weird tale, but one subjected to modernist techniques of compression and collage. The result is so elliptical that it is as if the text — part-obliterated by silt, mildew and algae — has been fished out of the Manchester ship canal which Steve Hanley’s bass sounds like it is dredging.

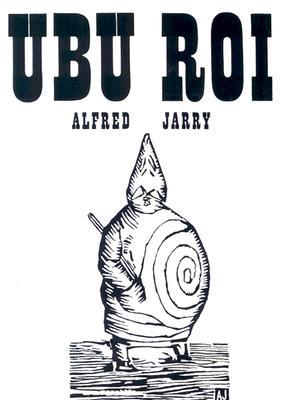

There is certainly laughter here, a renegade form of parody and mockery that one hesitates to label satire, especially given the pallid and toothless form that satire has assumed in British culture in recent times. With The Fall, however, it is as if satire is returned to its origins in the grotesque. The Fall’s laughter does not issue from the commonsensical mainstream but from a psychotic outside. This is satire in the oneiric mode of Gillray, in which invective and lampoonery becomes delirial, a (psycho)tropological spewing of associations and animosities, the true object of which is not any failing of probity but the delusion that human dignity is possible. It is not surprising to find Smith alluding to Jarry’s Ubu Roi in a barely audible line in “City Hobgoblins”: “Ubu le Roi is a home hobgoblin.” For Jarry, as for Smith, the incoherence and incompleteness of the obscene and the absurd were to be opposed to the false symmetries of good sense. We could go so far as to say that it is the human condition to be grotesque, since the human animal is the one that does not fit in, the freak of nature who has no place in the natural order and is capable of re-combining nature’s products into hideous new forms.

There is certainly laughter here, a renegade form of parody and mockery that one hesitates to label satire, especially given the pallid and toothless form that satire has assumed in British culture in recent times. With The Fall, however, it is as if satire is returned to its origins in the grotesque. The Fall’s laughter does not issue from the commonsensical mainstream but from a psychotic outside. This is satire in the oneiric mode of Gillray, in which invective and lampoonery becomes delirial, a (psycho)tropological spewing of associations and animosities, the true object of which is not any failing of probity but the delusion that human dignity is possible. It is not surprising to find Smith alluding to Jarry’s Ubu Roi in a barely audible line in “City Hobgoblins”: “Ubu le Roi is a home hobgoblin.” For Jarry, as for Smith, the incoherence and incompleteness of the obscene and the absurd were to be opposed to the false symmetries of good sense. We could go so far as to say that it is the human condition to be grotesque, since the human animal is the one that does not fit in, the freak of nature who has no place in the natural order and is capable of re-combining nature’s products into hideous new forms.

The sound on Grotesque is a seemingly impossible combination of the shambolic and the disciplined, the cerebral-literary and the idiotic-physical. The album is structured around the opposition between the quotidian and the weird-grotesque. It seems as if the whole record has been constructed as a response to a hypothetical conjecture. What if rock and roll had emerged from the industrial heartlands of England rather than the Mississippi Delta? The rockabilly on “Container Drivers” or “Fiery Jack” is slowed by meat pies and gravy, its dreams of escape fatally poisoned by pints of bitter and cups of greasy-spoon tea. It is rock and roll as working men’s club cabaret, performed by a failed Gene Vincent imitator in Prestwich. The what if? speculations fail. Rock and roll needed the endless open highways; it could never have begun in England’s snarled-up ring roads and claustrophobic conurbations.

It is on the track “The N.W.R.A.” (“The North Will Rise Again”) that the conflict between the claustrophobic mundaneness of England and the grotesque-weird is most explicitly played out. All of the album’s themes coalesce in this track, a tale of cultural political intrigue that plays like some improbable mulching of T.S. Eliot, Wyndham Lewis, H.G. Wells, Philip K. Dick, Lovecraft and le Carré. It is the story of Roman Totale, a psychic and former cabaret performer whose body is covered in tentacles. It is often said that Roman Totale is one of Smith’s “alter-egos”; in fact, Smith is in the same relationship to Totale as Lovecraft was to someone like Randolph Carter. Totale is a character rather than a persona. Needless to say, he in no way resembles a “well-rounded” character so much as a carrier of mythos, an inter-textual linkage between Pulp fragments:

So R. Totale dwells underground / Away from sickly grind / With ostrich head-dress / Face a mess, covered in feathers / Orange-red with blue-black lines / That draped down to his chest / Body a tentacle mess / And light blue plant-heads.

The form of “The N.W.R.A.” is as alien to organic wholeness as is Totale’s abominable tentacular body. It is a grotesque concoction, a collage of pieces that do not belong together. The model is the novella rather than the tale and the story is told episodically, from multiple points of view, using a heteroglossic riot of styles and tones: comic, journalistic, satirical, novelistic, it is like Lovecraft’s “Call of Cthulhu” re-written by the Joyce of Ulysses and compressed into fifteen minutes. From what we can glean, Totale is at the centre of a plot — infiltrated and betrayed from the start — which aims at restoring the North to glory, perhaps to its Victorian moment of economic and industrial supremacy; perhaps to some more ancient pre-eminence, perhaps to a greatness that will eclipse anything that has come before. More than a matter of regional railing against the capital, in Smith’s vision the North comes to stand for everything suppressed by urbane good taste: the esoteric, the anomalous, the vulgar sublime, that is to say, the weird and the grotesque itself. Totale, festooned in the incongruous Grotesque costume of “ostrich head-dress”, “feathers/orange-red with blue-black lines” and “light blue plant-heads”, is the would-be Faery King of this weird revolt who ends up its maimed Fisher King, abandoned like a pulp modernist Miss Havisham amongst the relics of a carnival that will never happen, a drooling totem of a defeated tilt at social realism, the visionary leader reduced, as the psychotropics fade and the fervour cools, to being a washed-up cabaret artiste once again.

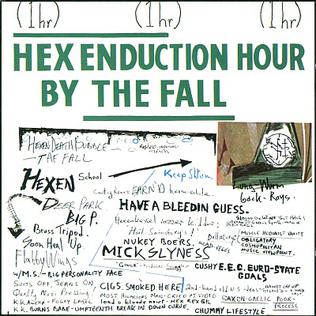

Smith returns to the weird tale form on The Fall’s 1982 album, Hex Enduction Hour, another record which is saturated with references to the weird. In the track “Jawbone and the Air Rifle”, a poacher accidentally causes damage to a tomb, unearthing a jawbone which “carries the germ of a curse / Of the Broken Brothers Pentacle Church”. The song is a tissue of allusions to texts such as M.R. James’ tales “A Warning to the Curious” and “Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad”, to Lovecraft’s “The Shadow over Innsmouth”, to Hammer Horror, and to The Wicker Man — culminating in a psychedelic/psychotic breakdown, complete with a torch-wielding mob of villagers:

He sees jawbones on the street / advertisements become carnivores / and roadworkers turn into jawbones / and he has visions of islands, heavily covered in slime. / The villagers dance round pre-fabs / and laugh through twisted mouths.

“Jawbone and the Air Rifle” resembles nothing so much as a routine by the British comedy group the League of Gentlemen. The League of Gentlemen’s febrile carnival — with its multiple references to weird tales, and its frequent conjunctions of the laughable with that which is not laughable — is a much more worthy successor to The Fall than most of the musical groups who have attempted to reckon with their influence.

The track “Iceland”, meanwhile, recorded in a lava-lined studio in Reykjavik, is an encounter with the fading myths of North European culture in the frozen territory from which they originated. Here, the grotesque laughter is gone. The song, hypnotic and undulating, meditative and mournful, recalls the bone-white steppes of Nico’s The Marble Index in its arctic atmospherics. A keening wind (on a cassette recording made by Smith) whips through the track as Smith invites us to “cast the runes against your own soul”, another M.R. James reference, this time to his story, “Casting the Runes”. “Iceland” is a Twilight of the Idols for the retreating hobgoblins, cobolds and trolls of Europe’s receding weird culture, a lament for the monstrosities and myths whose dying breaths it captures on tape:

Witness the last of the god men

A Memorex for the Krakens

If the measure of writing is to get as close as we can to the truth of existence, I know I will never write a

To accompany his latest piece with Tariq Goddard in The Quietus on True Detective Season 4 and the legacy of In The Dust of This Planet, Eugene

As another turbulent year draws to a close, the Repeater team put forward their favourite reads for the festive season. Publisher, Editor, and Author Tariq

If the measure of writing is to get as close as we can to the truth of existence, I know I will never write a

To accompany his latest piece with Tariq Goddard in The Quietus on True Detective Season 4 and the legacy of In The Dust of This Planet, Eugene

As another turbulent year draws to a close, the Repeater team put forward their favourite reads for the festive season. Publisher, Editor, and Author Tariq