Brad Evans: I Know I Will Never Write a Better Book

If the measure of writing is to get as close as we can to the truth of existence, I know I will never write a

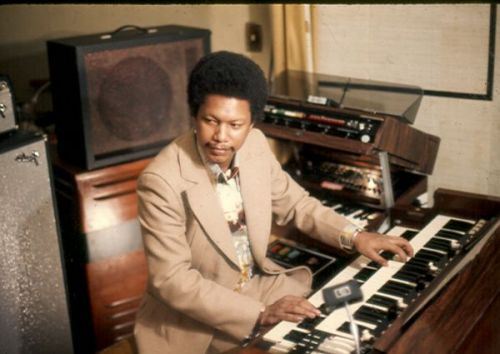

October marks the Black History Month in the UK, and in its honor we selected an extract from Decolonial Daughter: Letters from a Black Woman to her European Son by Lesley-Ann Brown. In this extract, the author talks about her father and his origins growing up in Trinidad.

Even when under the tyranny of my father and despite my youth, I understood his rage. If you are Black and you grow up in America, you do not have the “privilege” of not thinking about history and race. I say “privilege” because as far as I am concerned, it cannot truly be a privilege to get only a fraction of the story. From the lack of or very limited representation of Blacks in the media, to the very segregated housing arrangements that still overwhelming rules the day in the US, race was nothing I could claim I did not see.

However, let me pull forth the beauty that I experienced, the beauty that insists despite. There’s the beauty of little brown girls, sitting between each other’s knees as their hair is braided, much like when I braid your own hair. In this act we learn about the magic that is our hair, the beauty, the strength, the tenacity of spirit and of perseverance. When I braid your hair, I am taken back to Brooklyn and reminded of the beauty of brown girls jumping double-dutch, the jazz my father created in the living room, the comfort of sitting on my mother’s lap, of hearing my sister spin yet another bedtime story for me, of my brother teaching me how to ride a bike.

Your grandfather is what happens to so many of us who are the descendants of a conquered people. As the great American writer and poet Langston Hughes once wrote: “What happens to a dream deferred?”7 As Hughes’ poem goes on to wonder, your grandfather, Darlington Brown, exploded.

But before he did, this is his story. I share this story with you, son, only so that you can understand and appreciate the path that has been paved before you. Out of this darkness, your being can be rooted and fertilised. It is important that we remember both the stories of light and those of darkness, and understand that there are lessons to be gleaned from both. It is important that we do not forget these fallen fathers, the men who have come before us, as much as the women. May this story do him justice.

Darlington Brown, or “D.B.” or “Chief,” as he was affectionately called by his crew of friends, was originally from, as mentioned before, an area known derisively as “behind the bridge.” This is an area in the capital of Trinidad, Port of Spain. “Behind the bridge” is a ghetto where the descendants of enslaved Africans paved their own way. And like all other areas dominated by Africans, it is a centre of cultural signifi cance. I am writing these words not just for you son, but to everyone who is from this region and who may be reading my words now. Your grandmother, my mother, once took me there. In Music from Behind the Bridge: Steelpan Aesthetics and Politics in Trinidad and Tobago, author Sharon Dudley shares steelband historian Felix Blake’s words on the socio-cultural concept of “behind the bridge”:

“Behind the bridge” is, geographically speaking, anywhere East of the Dry River which randomly provides a line of demarcation between the city of Port-of-Spain and its Eastern suburbs nestling jauntily on the hills of Laventille […] The other meaning of “behind the bridge” is profoundly sociological, providing clear reference to a person’s socio-economic standing as poor, under-privileged and dispossessed—classic profi le of the Afro-Trinidadian whose ex-slave forebears[sic] had settled in the hills of Laventille and who, three generations later, was still society’s outcast…

It is from behind the bridge that the youth engaged in stick-fighting or Calinda, a martial art, and Limbo — of which Sonjah Stanley Niaah writes in her book Dancehall: From Slave Ship to Ghetto:

The Limbo dance, for example, highlights the importance of not only the historical but also the spatial imagination. As a consequence of lack of space on slave ships, the slaves bent themselves like spiders. Incidentally, the lack of space in slave dungeons such as Elmina Castle, with characteristically low thresholds that the enslaved navigated to move from dungeon to holding room to the “door of no return” (now renamed the “door of return”) before boarding the slavers is also obvious to the visitor. In the dance, consistent with certain African beliefs, the whole cycle of life is reflected. The dancers move under a pole that is consistently lowered from chest level and they emerge, as in the triumph of life

over death as their heads clear the pole […] The slaveships, like the plantation and the city, reveal(ed) particular spaces that produce(d) magical forms of entertainment and ritual.

It is from behind the bridge that creative resistance was born, midwifi ng Trinidad and Tobago’s world-renowned Carnival and steelpan, which was born out of the banning of drumming in 1884. Our drumming was banned because the British feared the coded messages being transferred through them; they feared that uprisings would be instigated. Our drumming that kept us close to Africa, that kept us close to the culture from which we came, was deemed illegal, like so many other aspects of our lives. It astounds me how much we as a people have been and continue to be policed, from our music to our hair to our movement. Has there ever been a group of people under more social control than Black people around the world?

If the measure of writing is to get as close as we can to the truth of existence, I know I will never write a

To accompany his latest piece with Tariq Goddard in The Quietus on True Detective Season 4 and the legacy of In The Dust of This Planet, Eugene

As another turbulent year draws to a close, the Repeater team put forward their favourite reads for the festive season. Publisher, Editor, and Author Tariq

If the measure of writing is to get as close as we can to the truth of existence, I know I will never write a

To accompany his latest piece with Tariq Goddard in The Quietus on True Detective Season 4 and the legacy of In The Dust of This Planet, Eugene

As another turbulent year draws to a close, the Repeater team put forward their favourite reads for the festive season. Publisher, Editor, and Author Tariq