A Leaving Statement from Tariq Goddard, a Founder and Editor of Repeater and Zer0 Books

Repeater and Zero Books are publishing imprints that have become a culture. That culture will endure longer than the individuals that helped bring it about,

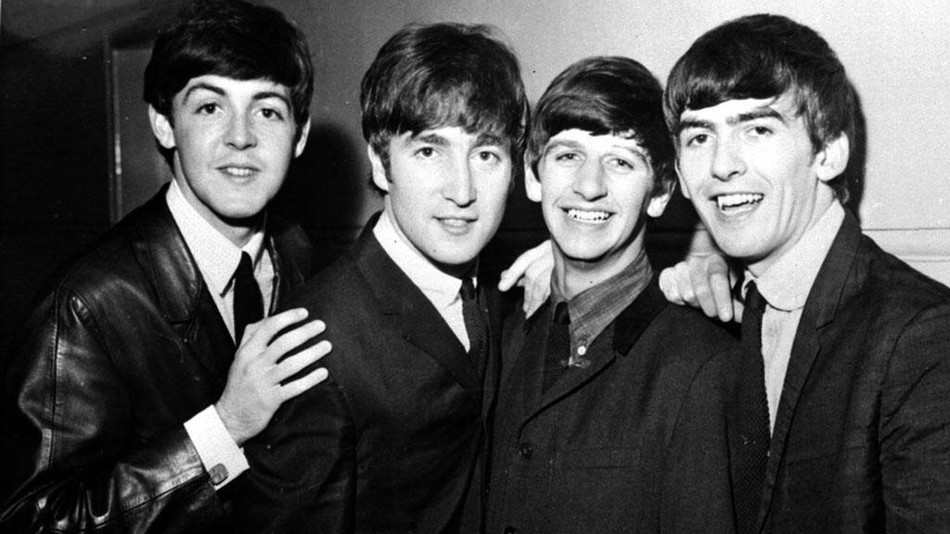

Fifty years ago, on 26 August 1968, the Beatles released their highest selling 45 rpm — the “Hey Jude”/“Revolution” single. While Paul McCartney’s “Hey Jude” garnered the most attention and is commonly regarded as one of the Beatles’ most perfect songs, John Lennon’s “Revolution” is arguably the song with the most interesting story in terms of its politics, and its afterlife in one of the most seminal and successful advertisements of all time.

“Revolution” was composed by John in Rishikesh in India where the Beatles were meditating with the Maharishi following a tumultuous year which saw their manager, Brian Epstein, commit suicide, and in which they had encountered extraordinary opprobrium from the far-right in the USA, who bitterly resented John’s off-hand statement that the Beatles had become “bigger than Jesus”. While the Beatles meditated, the global politics of 1968 exploded: Martin Luther King was murdered, the violent Prague Spring marked a turning point in Soviet history, the American War in Vietnam raged on, the Cultural Revolution was afoot in China and major riots and protests erupted in London, Mexico City, and, most notably, Paris. John decided that the time had come to explicitly address politics, as he explained, “I wanted to say my piece about revolution. I wanted to tell you or whoever listens and communicate, to say ‘What do you say? This is what I say’”.

At this time the Beatles were transforming from loveable mopheads who toured singing romantic jingles into studio-based psychedelic avant-garde bohemians. They were moving away from boy-girl love songs and towards evangelising about romantic philosophy, as marked by songs like “Strawberry Fields Forever”, “Fool on the Hill” and “Nowhere Man”. While each of these songs were intended as interventions into how people should live their lives, none of them were directly political. Indeed within 1968, the very idea of political pop music was a rarity and mostly something edged towards by “underground” bands like the Doors and Jefferson Airplane.

“Revolution”, John’s step into direct political expression, takes the form of an imagined dialogue between himself and a would-be revolutionary. However the latter remains silent, and instead we hear John’s numerous rebuttals. Each verse begins with refrains of limited agreement from John such as, “You say you want a revolution, well we wall want to change the world”. In each third refrain, John establishes his critical distance and sings “but if you’re talking about minds that hate, all I can tell you brother is you’ll have to wait” as well as the famous line “But if you carrying pictures of Chairman Mao, you ain’t gonna make it with anyone anyhow”. Then follows repetitions of the line “don’t you know it’s gonna be alright?” The song was recorded in London’s Trident Studio in a slow bluesy version with John lying down to sound more meditative. Interestingly, in one line he sings “But when you talk about destruction, don’t you know you can count me out… in”, suggesting that he was ambivalent about his actual political stance. Disagreement followed between the band over the song’s commercial potential and eventually John agreed to re-arrange the song into a more hard rock upbeat version despite his concern that the lyrics would now be more difficult to understand. The faster version was far harder than the norm in the 1960s; as producer George Martin recounted, “We got into distortion on that, which we had a lot of complaints from the technical people about. But that was the idea: it was John’s song and the idea was to push it right to the limit. Well, we went to the limit and beyond”.

The fast version, in which John does not sing “count me out.. in” but simply “count me out”, was released as the single alongside “Hey Jude”, while the original slow version appeared on the White Album, which was released later that year. A third version also appeared on the White Album named “Revolution No. 9”, though it bears little resemblance to the other two versions. It is in fact a scramble of electronic sounds and nonsensical phrases (“take this brother, may it serve you well”, “the twist, the Watusi”). John later told the press that the sounds of “Revolution No. 9” were meant to mimic what actual revolution would sound like.

Upon release, the “Hey Jude”/“Revolution” (featuring the rock version) record rocketed to huge success, selling eight million copies and being their most successful 45rpm ever. Within the media, attention fixated upon “Hey Jude”, which was widely acclaimed. “Revolution”, by contrast, received little attention: for example, the Record Mirror review simply wrote “flipside: pacier, punchy but on a less spectacular scale”, while Record Retailer managed to be even more concise “flip: faster, more compact”. When the White Album was released later that year, “Revolution No. 1”, the original version, also received little commentary (the Melody Maker reviewer wrote “it’s different, softer, with the words clear”). “Revolution No. 9”, however, attracted plenty of criticism, with the same critic declaring: “There is, in fact, no music in this cacophony of sound: the sort of noise you get when you spin the selection along the short wave at two in the morning. Noisy, boring and meaningless, which can only be some private joke for the Beatles’ inner circle.”

If the mainstream music media were largely unmoved by “Revolution”, the reaction within the leftist press was a stark contrast, as they seemingly went into competition with each other in search of harshest condemnation. Ramparts declared “Revolution preaches counter-revolution”, the New Left Review called it a “lamentable petty bourgeois cry of fear”, the Village Voice wrote “It is puritanical to expect musicians, or anyone else, to hew the proper line. But it is reasonable to request that they do not go out of their way to oppose it.” The Berkeley Barb sneered “Revolution sounds like the hawk plank adopted in the Chicago convention of the Democratic Death Party”. Black Dwarf dismissed the song as “no more revolutionary than Mrs. Dale’s Diary” (Lennon wrote in response saying “I don’t remember saying Revolution was revolutionary — fuck Mrs Dale”). However some critics attempted more ambiguous interpretations, for instance Greil Marcus wrote, “The music contained a message of its own, a message of its own, a message of its own, a message of excitement and freedom, which works against sterility and repression in the lyrics… The music doesn’t say ‘cool it’ or ‘don’t fight the cops’”. Other notable responses to “Revolution” include Nina Simone’s parody re-writing of the song to insist upon immediate revolution, while Charles Manson’s “Family”, in their build-up to their vicious homicides, parsed over every cut in the White Album with “Revolution No.1”, in particular, apparently telling them that the time for peace and love was over.

So how are we to assess “Revolution” today? In the context of the Beatles’ wider political commitment to love as the ultimate revolutionary force (best exemplified in the song “All You Need is Love”), it might be more astute to regard the song as an instance of what Jeremy Gilbert refers to as “acid communism”; a sort of tactical commitment to the revolutionary potential of yoga, meditation, veganism, sexuality, drug consumption, etc., rather than anti-leftist counter-revolutionary politics, as it was regarded by some at the time. Moreover, the various iterations of “Revolution” might each be regarded as very different types of political statement. As per Greil Marcus’s review, which notes how the hard rock arrangement seems to contradict the “repressed” lyrics, we might ponder the problem of how political content appears in popular music. Popular music theorists like John Scannell, for instance, note the affective capacity of popular music is often most intensively experienced at a physical level (i.e. it might make us want to dance in a particularly sexually charged way) and that this somatic capacity can be more meaningful than the content of the lyrics, leaving us with the possibility of a far more ambiguous reading of the song. Indeed given Lennon’s own ambivalence, most explicitly expressed in “count me out… in” lyrics as well as the alternative renderings of the song, we might best conclude that “Revolution” is a song probably best not read beyond its own ambivalences. Yet the song is often heralded by the right, listed for example, as one of the great conservative rock songs by National Review, and used in the campaign trail by none other than Donald Trump himself. This is partially because the song’s history was only beginning in 1968.

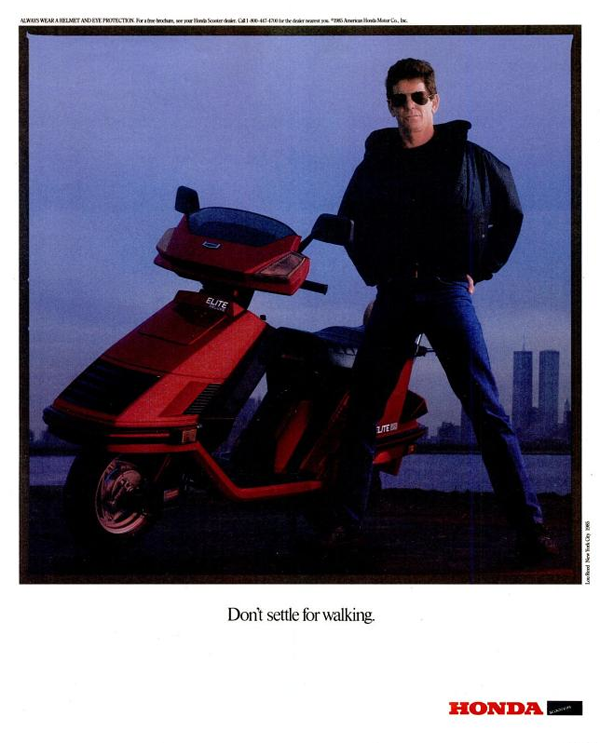

By the 1980s, an era in which the so-called “flower power” of Sixties idealism was being superseded by materialism and yuppy culture, and which began with John Lennon being violently shot to death outside his home, “Revolution” was about to receive a new lease of life when the Oregon-based advertising agency Wieden+Kennedy sought to use the song in an advertisement to launch a new air bubble gimmick for Nike shoes. Wieden+Kennedy had just succeeded in using Miles Davis and Lou Reed songs in their adverts (an ad for Honda scooters using “Walk on the Wild Side” finished with Lou, sitting on a scotter wondering “why bother walking?”) and they clearly relished the challenge of being the first agency to obtain permission to use an original recording by the Beatles. In selecting the song, the agency had departed far from the brief, which was grounded in having a straight-forward product-centred ad, yet when the idea was pitched to Nike, the client’s response was “You’ve given me my Lou Reed!”

The process of obtaining permission was complex, unlike other campaigns where it was possible to use Beatles songs in ads in the form of cover versions — for example, “Taxman” was used by H&R Black tax advisers ¾ but obtaining the rights to use a Beatles’ original recording was another matter. In 1985, Michael Jackson had outbid Paul McCartney to buy the performance rights to a whole catalogue of Beatles songs and it was his representatives who contacted Yoko Ono to solicit approval on behalf of Wieden+Kennedy. Ono, it seems, managed to persuade Capitol/EMI to release permission. Janet Champ, who was part of the team that came up with the idea of using “Revolution” for the spot, remembered the matter as follows:

What made me feel really good about having this spot was we wrote Yoko Ono and we went and told her what the idea was — I didn’t get to go, but we sent the idea to her and we asked her what she thought about it — and she loved it… And the Beatles were all behind it, too, so once they said it was all right, we felt pretty good about it”.

Ono later explained to Time magazine that she didn’t “want to see John deified” nor for “John’s songs to be part of a cult of glorified martyrdom” but instead to be enjoyed by a “new generation”, “to make it part of their lives instead of a relic of the distant past”. The deal reportedly amounted to $250,000 for EMI and another $250,000 to SBK Entertainment World for the copyright and entailed a media campaign that cost between $7 and $10 million. The deal complete, Janet Champ recalled the day EMI’s master tape of the Beatles recording arrived at the agency in Portland:

We had the master tape right in our hands of the song and we got to put it on and hear all the mistakes and you know [reverent pause] the actual master right out of the vault from Abbey Road and they played it on separate little speakers so you could hear when Ringo dropped the drumstick or somebody made a mistake and it was so beautiful and clear. And everybody in the recording studio came in, came out of the halls all the way down to this rom to hear this for the first time. That was a great moment.

For Nike, who commissioned the ad, the stakes were enormous, and it was their first step into major scale TV advertising. Their sales were plummeting, largely due to Reebok absorbing market share as part of the 1980s aerobics fad. Reebok’s sales had risen from $3.5 million in 1982 to a staggering $307 million by 1987, leaving Nike reeling. Nike CEO Phil Knight recalled the moment as follows:

Until then, we really didn’t know if we could be a big company and still have people work closely together. Visible Air was a hugely complex product whose components were made in three different countries, and nobody knew if it would come together. Production, marketing, and sales were all fighting with each other, and we were using TV advertising for the first time. There was tension all the way around. We launched the product with the Revolution campaign, using the Beatles song. We wanted to communicate not just the a radical departure in shoes but a revolution in the way Americans felt about fitness, exercise, and wellness.

The ad was edited by Paula Greif and Peter Kagan, who had just been nominated for best editing, best cinematography, and best art direction at the 1987 Video Music Awards. Notes from post-production meetings indicate that an overall theme in “revolution in fitness lifestyle” was being sought but it was about “feeling good”, not “looking good”, and hence a frame with a man combing hair was removed. “Unfortunately , NIKE is a ‘macho’ company,” the notes read, so the original opening frames of three shots of women were eliminated.

Like the original three songs, there are three versions of Nike’s Revolution — two were hard-rock versions, with one softer version with doo-wops. It was the hard rock version that was the major spot and it consisted of very jerky black-and-white hand-held camera film, with a few archival inserts, that shows Nike athletes and ordinary people participating in a variety of sports at various levels of seriousness. There are whites, blacks, men, women, and a toddler. A woman plays air guitar and a huge laughing crowd runs into the ocean. As Scott Bedbury, who later became Nike’s advertising director described it, the most striking image was the toddler

running with his arms raised out in front of him, legs turning as fast as they could to keep pace with his upper body. His torso was tipping forward as only a toddler’s can, when discovering what it’s like to run full out for the first time. These images were not merely evocative and beautiful but meaningful, particularly in juxtaposition to each other. The message behind this medley of images marked a new outlook for Nike: the Nike brand now spoke to old as well as young, to women as well as men, to world-famous champions and obscure street athletes, using different images but the same voice.

The ad can be interpreted as offering a theme of empowerment and transcendence and a personal philosophy of everyday life, and part of the ad’s success is how this philosophy is reinforced by the song. The clip from “Revolution” includes the opening guitar barrage and the closing yelps of “alright”, but only a few lyrics: “you say you want a revolution, well, you know, we all want to change the world… But if you talk about destruction, don’t you know that you can count me out.”

The ad was a massive success — Nike orders increased by 30% immediately and sales doubled over the next two years. Moreover, Nike and Wieden+Kennedy had struck marketing gold, and the ad’s philosophy of empowerment and a personal philosophy of everyday life became the basis of their marketing positioning for the coming decade and laid the foundations for Nike to become one of the true giants of branding. As the sociologists Robert Goldman and Stephen Papson argued, from that point onwards, Nike and Wieden+Kennedy started to stand out in what they described as the cultural economy of images. The sheer scale of their domination within this supposed “sign economy” is staggering to behold. By 1991, Nike held 29% of the global athletic shoe market and its sales had exceeded $3 billion. Indeed Wieden+Kennedy, a small rookie agency, had finally established themselves as a major player in global advertising at the vanguard of the creative side of the industry.

Yet the use of “Revolution” by the Beatles attracted controversy too. Time magazine wrote “Mark David Chapman killed him. But to took a couple of record execs, one sneaker company and a soul brother to turn him into a jingle writer”. The Chicago Tribune described the ad as “when rock idealism met cold-eyed greed” and the New Republic commented “The song had a meaning that Nike is destroying”. Yet what meaning Nike was destroying was a puzzle. A rock critic for the LA Reader wrote “When Revolution came out in 1968 I was getting teargassed in the streets of Madison. The song is part of the soundtrack of my political life. It bugs the hell out of me that it has been turned into a shoe ad”. John Doig, a creative director at Ogilvy & Mather, remembered anti-Vietnam demonstrations with “bloody police truncheons coming down and Revolution playing in the background. What that song is saying is a damned sight more important than flogging running shoes”. “Revolution”, it seems had apparently morphed considerably for some listeners from a “petty bourgeois cry of fear”, all catalysed by a sneaker spot.

The most significant response was the $15 million lawsuit filed by Apple Records against Nike, Wieden+Kennedy and Capitol Records in an attempt to half the airing of the commercial. Apple claimed that, even though Nike had legally obtained permission for the rights to the music, it had used the Beatles “persona and good will” without permission. This charge is peculiar given how the ad producers had understood that the Beatles themselves had apparently approved the spot. The explanation perhaps lies in the sequence of unsuccessful suits Apple Records had filed against Capitol/EMI, through which the Beatles’ company had attempted to regain control over royalties derived from new formats like CDs. Reportedly the action was settled confidentially and out of court, after the campaign had run its course. Later, Nike and Wieden+Kennedy used “Instant Karma”, a solo song by John Lennon, in an ad, perhaps reflecting its better relationship with Yoko Ono, while Apple, EMI and Capitol agreed that no Beatles version would ever be used again to sell products — truly the Nike Revolution was a one-off.

Despite the massive boost in sales for Nike, the critical attention generated by the ad appears to have festered on Nike with long-term consequences. Negative press coverage on Nike started to accumulate, focussing on its patriarchal culture, its labour abuses, the brand became accused of tempting young black kids into buying athletic shoes they couldn’t afford and even blaming Nike for occasional murders. By today, in anti-globalisation protests, Nike is typically identified as one of the most offending “bad apples” of the corporate world. Dating from the Revolution campaign, Nike emerged as a target: big enough, salient enough, and suspect enough to draw fire across a range of issues. The long-term impact of using John’s song was thus to attract attention from an audience poised for broad-scale critique.

We can recognise the moment of the Nike Revolution ad as having not just launched Nike into the stratosphere of brands, but also helping to concretise the everyday wearing of sports shoes. Writing these words thirty years later in a university library, it is striking to note that the majority of students come to study wearing shoes designed for professional sports activities. The fact that this apparently strikes nobody as even slightly odd speaks to how we are living in the legacy of extraordinary marketing campaigns and market transformations. Indeed, the possibility that so many people are wearing these shoes is because John Lennon, meditating in Rishikesh, decided to address the politics of 1968, reminds us that the collision of culture and politics in the medium of advertising creates the most unpredictable outcomes imaginable.

Alan Bradshaw is the author, with Linda Scott, of Advertising Revolution: The Story of a Song, from Beatles Hit to Nike Slogan.

Alan Bradshaw is the author, with Linda Scott, of Advertising Revolution: The Story of a Song, from Beatles Hit to Nike Slogan.

Repeater and Zero Books are publishing imprints that have become a culture. That culture will endure longer than the individuals that helped bring it about,

If the measure of writing is to get as close as we can to the truth of existence, I know I will never write a

To accompany his latest piece with Tariq Goddard in The Quietus on True Detective Season 4 and the legacy of In The Dust of This Planet, Eugene

Repeater and Zero Books are publishing imprints that have become a culture. That culture will endure longer than the individuals that helped bring it about,

If the measure of writing is to get as close as we can to the truth of existence, I know I will never write a

To accompany his latest piece with Tariq Goddard in The Quietus on True Detective Season 4 and the legacy of In The Dust of This Planet, Eugene