Brad Evans: I Know I Will Never Write a Better Book

If the measure of writing is to get as close as we can to the truth of existence, I know I will never write a

This is an edited extract from David Stubb’s 1996 & the End of History– available here and currently just £4.50 including UK postage in our half price World Cup sale.

1995 may have been the year that Britpop burst through, but 1996 was the year in which it loomed largest and was most overbearing, Oasis in particular, despite not releasing an album that year. 1996 was still a year of Conservative g overnment, but so commanding was Tony Blair’s lead in the polls it was clear he was Prime Minister elect. It was possible, in 1996, for him to bask in the unspoiled glow of his triumph in bringing the long Tory nightmare to an end, untarnished by the many compromised decisions he would make almost immediately on taking office in 1997, beginning by accepting a £1 million donation from Formula 1 supremo Bernie Ecclestone, only months later to grant exemption to the motor racing organisation from a general ban on cigarette advertising. All of that was to come; in 1996, he was still practically an honorary Oasis band member.

1996 was also the year of Euro ’96, in which English footballing hopes were bound up with the worlds of both comedy and music. It wasn’t just Baddiel and Skinner’s collaboration with The Lightning Seeds, “Three Lions”, but the sanguine, laddish, retrograde mood engendered by Britpop and Loaded. It wasn’t just football that was coming home, but the general sense that after the dark Seventies and the fragmented Eighties, Britain (led by England, of course) had rediscovered its mojo, the spring in its step, the spirit of Hurst and McCartney, the white heat of a bygone era.

The centrality of football was beyond dispute in 1996. The sport had endured a period in the doldrums during the 1980s, blighted by hooliganism and a lack of investment in infrastructure, which led to tragedies such as the Bradford stadium fire disaster in 1986 and Hillsborough in 1989, in which fifty-six and ninety-six fans died respectively; it’s only today that we can see the callous villainy that was a lurking cause in these dreadful events.

By the early 1990s, however, a series of events had combined to rehabilitate football: the progress of England at Italia 90 and the national communal paddling in the tears of Paul Gascoigne, a working class hero for post-working class times; the “gentrification” of football effected by Nick Hornby’s Fever Pitch, the confessions of an Arsenal lad which lifted the lid on the mentality of the football obsessive; and, most significantly of all, the vast sums of money invested in the game by Sky Sports. Football had become an integral preoccupation of the Nineties, in which essentially soft, polite, slightly unfit specimens of cosy manhood behaved “badly”, rather than viciously, no longer slumped on sofas drinking beer out the tin, wearing their pyjamas in the evening as they watched football rather than take their lives seriously.

Skinner and Baddiel’s Fantasy Football League epitomised this new spirit of laddishness, and the essential absurdity of football fandom, of getting so keyed up about which bunch of increasingly non-local professionals beat another to attain you bragging rights for something that had absolutely nothing to do with your own efforts, nor any bearing on anything. However, come Euro 96 and the Skinner/Baddiel/Broudie-penned anthem “Three Lions”, a fervent gleam entered Skinner’s eye in particular. There was a certain quiet clenching of the fists, a whitening of the knuckles. Actually, this really mattered. The phrase “coming home” had a real resonance. Where and why had we wandered since 1966?

Gazza would apparently sing Three Lions every morning during the tournament.

All the ducks seemed to be converging in a row. England, at full strength and automatically qualified, would be playing all of their games at Wembley Stadium, that hallowed site of British football, whose traditions stretched back to the very first FA Cup Final in 1923, when a white police horse attained immortality for its efforts in helping clear the pitch of fans who had spilled onto the turf. England-bashing had been a tabloid sport since the last days of Sir Alf Ramsey, and had reached a zenith three years earlier as the luckless Graham Taylor was depicted as a turnip for his failure to lead England to qualification in the 1994 World Cup. He had lacked key players such as Alan Shearer and Paul Gascoigne, but this was no excuse; with his odd way with words from the touch-line (“Do I not like that.” “Can we not knock it?”) he was perceived as the sort of bungling, regional jobsworth who had hampered England since the days of Will Hay, a small man who seemed to be subconsciously courting failure by selecting players like Carlton Palmer. Taylor was the butt of a peculiar trait in the mindset of the English patriot, who holds the dual belief that the country is the finest in the world (with all the entitlements that entails) and yet simultaneously going to the dogs.

Under Taylor, it was undoubtedly the latter. Under Terry Venables, it would be the former. A creature of the Sixties, where he had shone as a player for the stylish Spurs, Venables had co-written a TV series, Hazell, and felt like a fabled creature of cockney folklore, who could have stepped straight out of a Minder episode, or even a Blur song. He was a bit of a ducker and a diver who had made the blazers harrumph. Even before Euro 96 started, he had told the FA where they could stick the manager’s post after they tried to over-assert themselves with him. He would quit the job after the tournament. As it turns out, suspicions about his improprieties were well founded, as emerged in 1998 when he was disqualified as a company director for seven years. But no matter in 1996. He made the blazers harrumph and charmed journalists, players and the public alike.

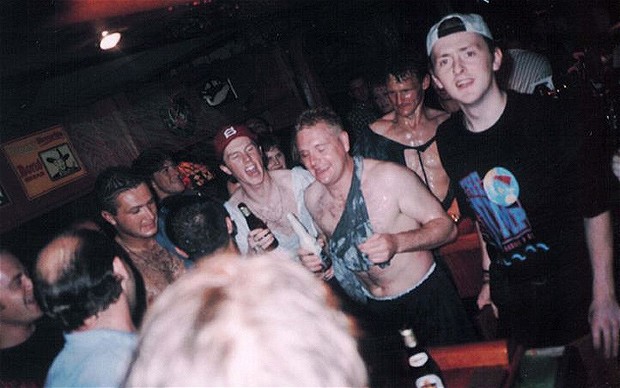

Not initially, however. There was a febrile return to the going-to-the-dogs narrative in a friendly match in Hong Kong during the run-up to the tournament. England had performed indifferently in a 1-0 victory against a local XI and Venables’ claim that the grass had been too long for the players’ liking had been branded “the most pathetic excuse ever” by the Mirror, which in 1982 would outdo even the Sun in its bipolar, nationalist histrionics. The real ire was reserved for Paul ‘Gazza’ Gascoigne, about whom the tabloids had never quite been able to make up their minds: stout fellow, cheeky chappie and salt of the earth, or hooligan, boorish scum? Pictures of his 29th birthday celebrations, which involved thousands of pounds’ worth of damage on a Cathay Pacific flight, were splashed across the front page of the Sun, who condemned Gazza as “a drunken oaf with no pride”. The lack of pride was the key point at this vital juncture; suspicions were already growing that these increasingly well-paid players thought more of playing for their clubs than of the allegiance they owed to their country. They appeared to be oblivious to the fact that they were carrying not just England’s footballing hopes but the esteem of a nation, yearning in the bright blue Nineties to pick up where they left off in the Swinging Sixties when we swung, granted, but swung sensibly. As an admonition, Sir Alf Ramsey was trundled out by the Mirror to write a column titled “I’d kick you out, Gazza”, in which he assured the player that his antics would not have been tolerated in his World Cup winning squad of 1966.

Simultaneously, the Mirror ran with the slogan, “WE DiD iT iN ’66, WE’LL DO iT iN ’96”, with Alf Ramsey balancing his remarks about Gazza’s dispensability with the observation that he could be “England’s match winner and inspiration”. Meanwhile, a piece in the Sun appeared under the by-line of England player Paul Ince, who wrote that: “The time has come for the footballing bull-dog breed of old England to strike back. Patriot missiles if you like… This team is good enough to inherit the fame of Sir Alf’s boys.” The phrase “patriot missiles” was an interesting one; it had become familiar to TV spectators of the first Gulf War of 1991, in reference to the missiles used to repel Saddam Hussein’s Scud missiles. The Brits had been heavily involved in that war with Operation Granby; this was the New World Order, in which war was no longer stupid, as Eighties Boy George had insisted, but a liberal imperative – one in which Britain would play a starring and benevolent role. The Cold War had ended, but the spirit of bellicosity continued to glow hard, and nowhere more so than in discussing England’s sporting chances.

England made an inauspicious start to the tournament, only managing a draw with relatively lowly Switzerland. Alan Shearer, bullet-headed epitome of English pride, scored, but then they had allowed the Swiss back into the game and they equalised with a penalty. Next up were Scotland, and the same pattern was repeated, with a goal by Shearer, followed by a clumsy tackle by Tony Adams, donkey to Taylor’s turnip in the tabloid fables of folly, and here we went again. Except England’s Seaman saved the penalty, and in the blink of an eye a peroxided Gazza received the ball upfield, looped it over the head of doughty Scottish defender Hendry and then angled it expertly into the bottom left hand corner. Vindication for the “drunken oaf ”, whose immediate reaction was to parody tabloid pictures of him being plied with drink. No apology for his high jinks; it was as though vodka and carousing lent him his élan on the pitch.

In the final game of the group stages, England met Holland. This was a grudge match of sorts since, thanks to some dubious refereeing, Holland had beaten England 2-0 to deny them their place in the 1994 World Cup. However, those of us watching imagined a difficult game, which England might just shade if they were lucky but in which a draw would be respectable. Instead, England’s stars tore the Dutch apart, the likes of Ince, Sheringham, Anderton, Shearer, and especially Gascoigne, playing to their maximum potential, threading past the opposition with an unexpected connectivity and panache that was frankly foreign, with Gascoigne the midfield orchestrator. This was one of the euphoric moments of the summer in which, fleetingly, notions of English preeminence did not seem delusional.

Spain in the quarter final was more fraught, with England lucky to make it to penalties. However, here again, something quite un-English happened that made one wonder, in a half-formed sort of way, if St George had acquired a special dispensation from the footballing Gods in the Heavens. England won, on penalties, with Stuart Pearce, who had famously missed his in 1990, taking up the ball determined to slay the dragon of that memory. As he cannoned the ball home, it was as if his courage were unscrewing from a terrible sticking point. His face,

normally a stoical blank, even when he had scored in an FA Cup Final in 1991 against Spurs, exploded through a range of unrepressed contortions; not just the expected “YEsss!!!!” but the sort of childlike frowny-frown that crosses a child’s countenance before it bursts into tears, as if in deep resentment at the injustice that he, proud Englishman Stuart Pearce, had had to wait so long for this moment. It was a moment of ugly/beautiful British emotion, a sense that something was bursting through at long last.

And so. Once more, Germany in the semi-final and a chance to make 1990 right. And 1972 and 1970, for that matter, previous tournaments in which the old vanquished Teutons had shown themselves to have assumed a palpable superiority against England that half made you entertain the suspicion that Germans were better than us at stuff, or something, or thought they were.

In 1996, the Mirror was under the editorship of Piers Morgan, who came across as someone desperately trying to be an authentic tabloid editor, like the middle class bloke trying to ingratiate himself with the regulars in a greasy spoon. As such, he miscalculated wretchedly. On the day of the match, his Mirror carried the headline, “Achtung! Surrender! For you, Fritz, the Euro 96 Campaign Is Over”, accompanied by an image of Stuart Pearce in the Tommy Atkins-style tin helmet of a British soldier. Even with a postmodern “patriotism” at large in the country, expressed ironically but with a genuine twinge, this was just plain crass, and failed to resonate with a nation whose generations of war evacuees were now of pensionable age. Terry Venables himself felt obliged to come out with a pointed public statement that this was just a football match, we’re not at war.

Still, there was a residue of frustration and anger at high-achieving, perhaps even lucky Germany, which was more about an English sense of under-achievement by comparison. And always, it seemed to be Germany standing in the way, not baby-bayonetting, rabid Nazi Germany, but unruffled, sophisticated, high-functioning, slightly effete, postwar Germany – Kraftwerk Germany. God, felt even I – a fan not just of Kraftwerk but Can, Neu, Faust, Herzog, Wenders, Stockhausen, WG Sebald – if only we could bloody beat Germany.

England lost on penalties to Germany; of course they did. When it came to cool and technique and self-confidence, they would always fall short, still more so in future tournaments, when they failed worse, not better. Because England was condemned to refuse not to be England.

At the end of the game, a small bloke sitting alone at an adjacent table took umbrage at the glum silence that settled on the pub. He rounded on us; “Well, c’mon, are we English or what? That was a fackin’ good effort. Give us a fackin’ round of applause, eh? Let’s fackin’ ’ave it!”

Types like us, part-time patriots, suffered similar “England expects” moments in the aftermath of the game. Nick Hornby recalled coming away from Wembley and being confronted by a “confrontational nutter” wrapped in the flag of St George, who approached him and his friends and asked, “Do you love England, lads? Do you really love England?” Expediently, they assured him that they did. “Well, fucking sing up for them, then”, he commanded.

We might have told our bloke where to stick his compulsory patriotism and mind his own business. But having so clearly been wracked with support for our national team, it would have been impossible, or at least hypocritical, to pretend we were above that sort of thing. We weren’t. And so, sheepishly, we did as we were told and applauded. It felt like a double defeat. In central London, there were two hundred arrests as angry, overheated fans, dehydrated by lager and frustration, went on the rampage. In Brighton, a seventeen year-old from Russia was stabbed several times on suspicion of being German. Never mind coming home – time to go home.

Later, in 1996, a hawkish, benign-looking fellow called Arsène Wenger, from the Alsace region in France, took over as manager of Arsenal FC. With a negligible playing history and looking more like he’d come to the club to head up the accounts department, he methodically set about eradicating the nutritional, training and extra-curricular habits which slowed and dulled the on-field performances of English professional players. No more Kit-Kats, gammon, steak, egg and chips washed down with squash and fizzy drinks and later several pints of lager, the diet of the average professional footballer. Instead, pasta, vegetables, boiled chicken. A season or so later, a fitter, speedier, more technically gifted Arsenal team would race to a Premier League and Cup double, cutting through their English opponents like lard. His methods would be widely copied. English football would cease to be English, except for international tournaments, at which the inbred technical weaknesses of homegrown players were exposed time after time, often by fellow English Premier League players from France, Portugal, Spain, Germany.

As for “Three Lions”, the German team sang it all the way back to the hotel after winning Euro 96 on a golden goal, as did their fans. The song eventually reached number sixteen in the German singles charts.

If the measure of writing is to get as close as we can to the truth of existence, I know I will never write a

To accompany his latest piece with Tariq Goddard in The Quietus on True Detective Season 4 and the legacy of In The Dust of This Planet, Eugene

As another turbulent year draws to a close, the Repeater team put forward their favourite reads for the festive season. Publisher, Editor, and Author Tariq

If the measure of writing is to get as close as we can to the truth of existence, I know I will never write a

To accompany his latest piece with Tariq Goddard in The Quietus on True Detective Season 4 and the legacy of In The Dust of This Planet, Eugene

As another turbulent year draws to a close, the Repeater team put forward their favourite reads for the festive season. Publisher, Editor, and Author Tariq